How is research integrity being taught in academic institutions in Europe? What are the main challenges faced by teachers instructing students about research integrity? How can the quality and efficacy of this teaching be improved? In an attempt to answer these questions, the team at University of Zurich – one of the partners in the H2020 INTEGRITY Project – conducted an online survey targeting scholars teaching research integrity across Europe – see the Deliverable 3.2 – Results of mapping current practice to get the full scope of the survey.

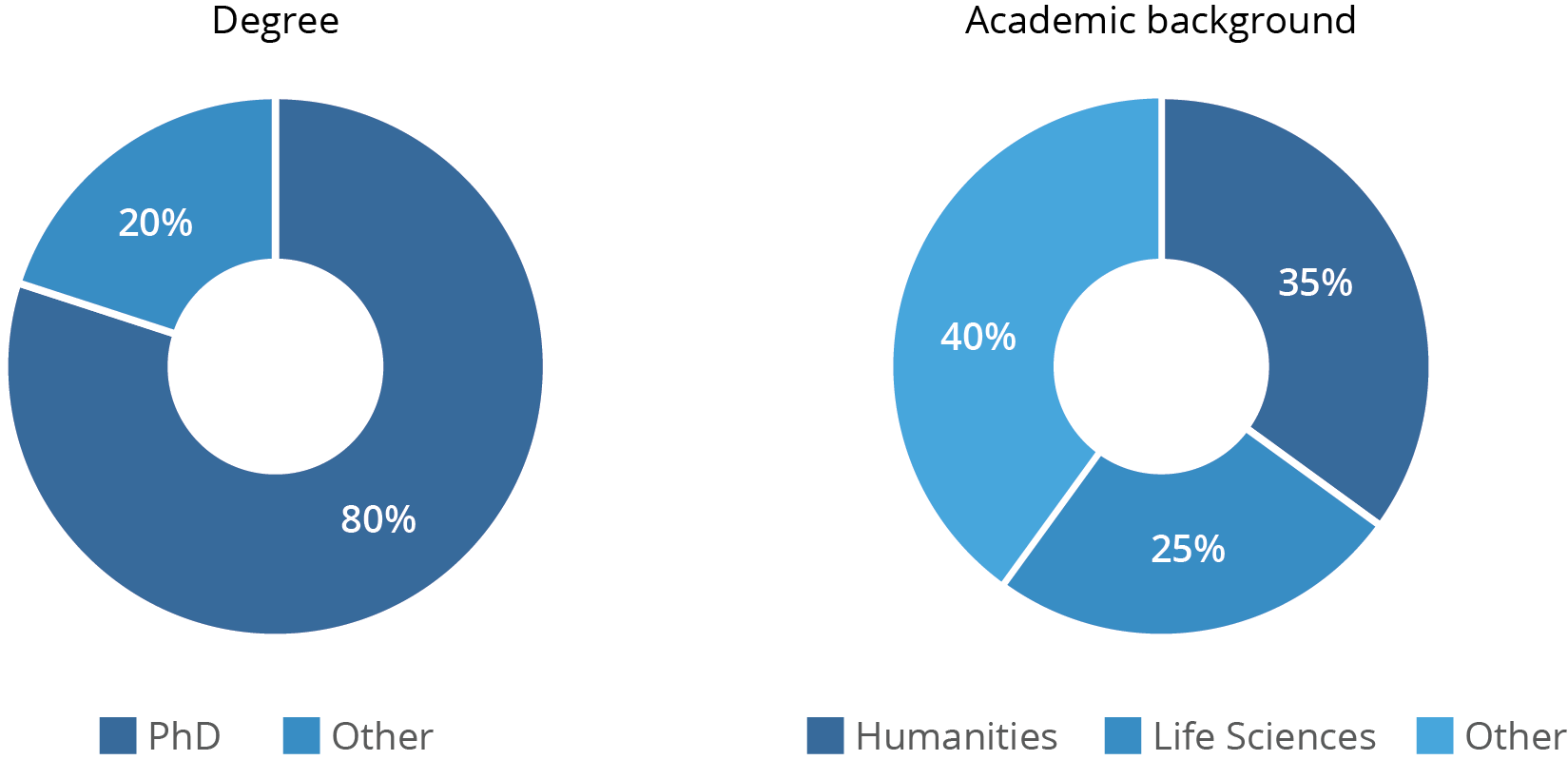

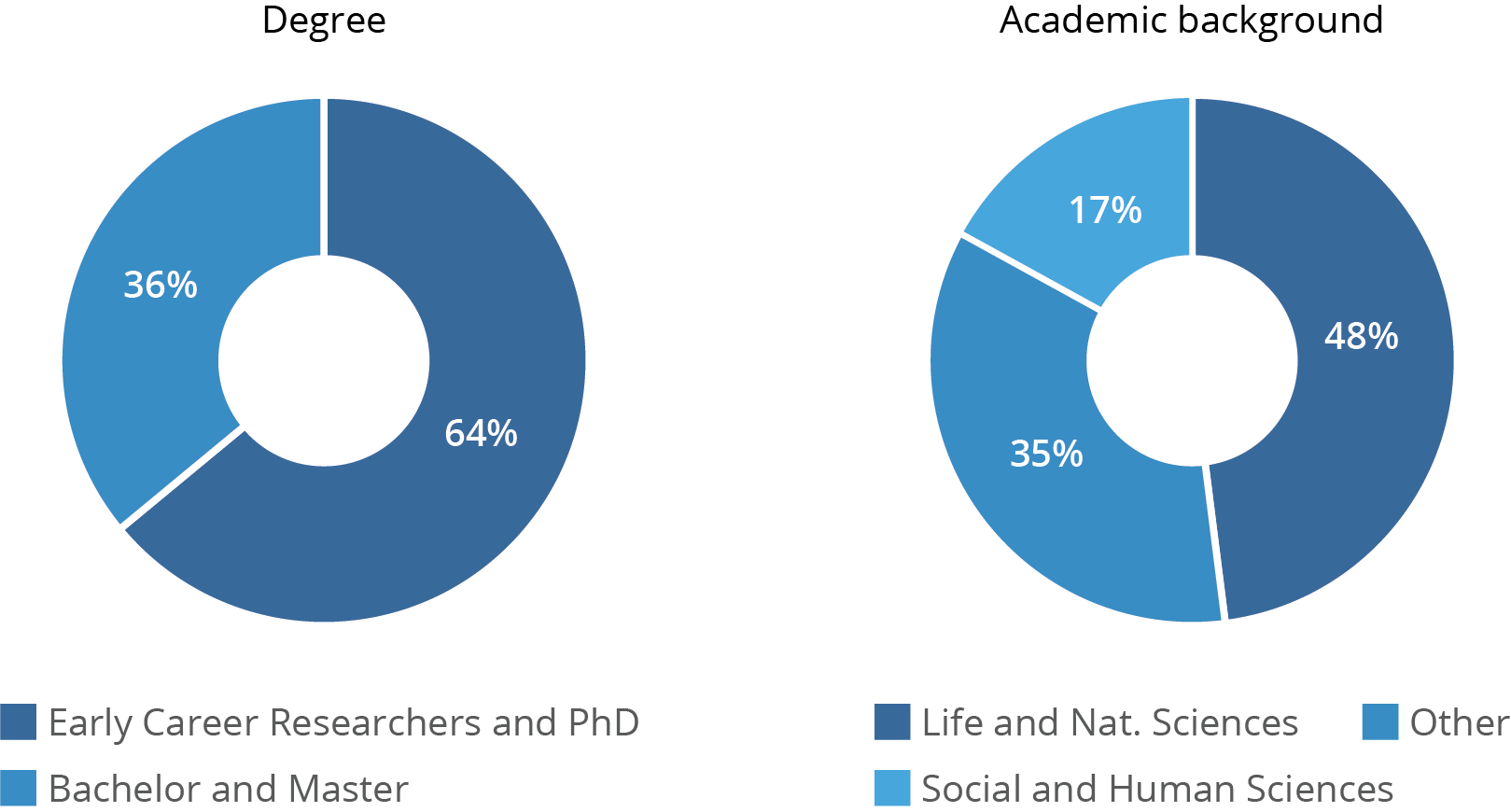

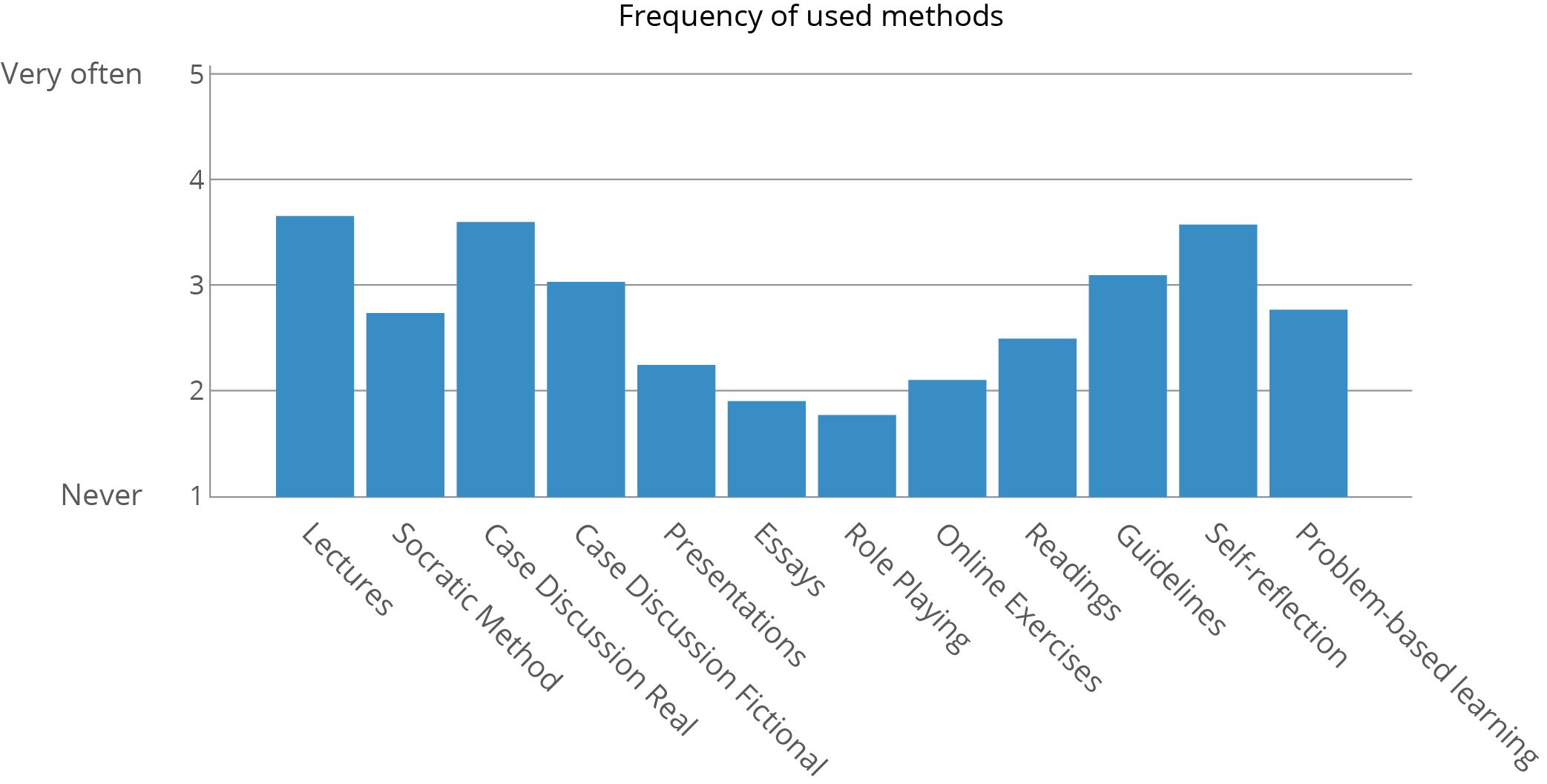

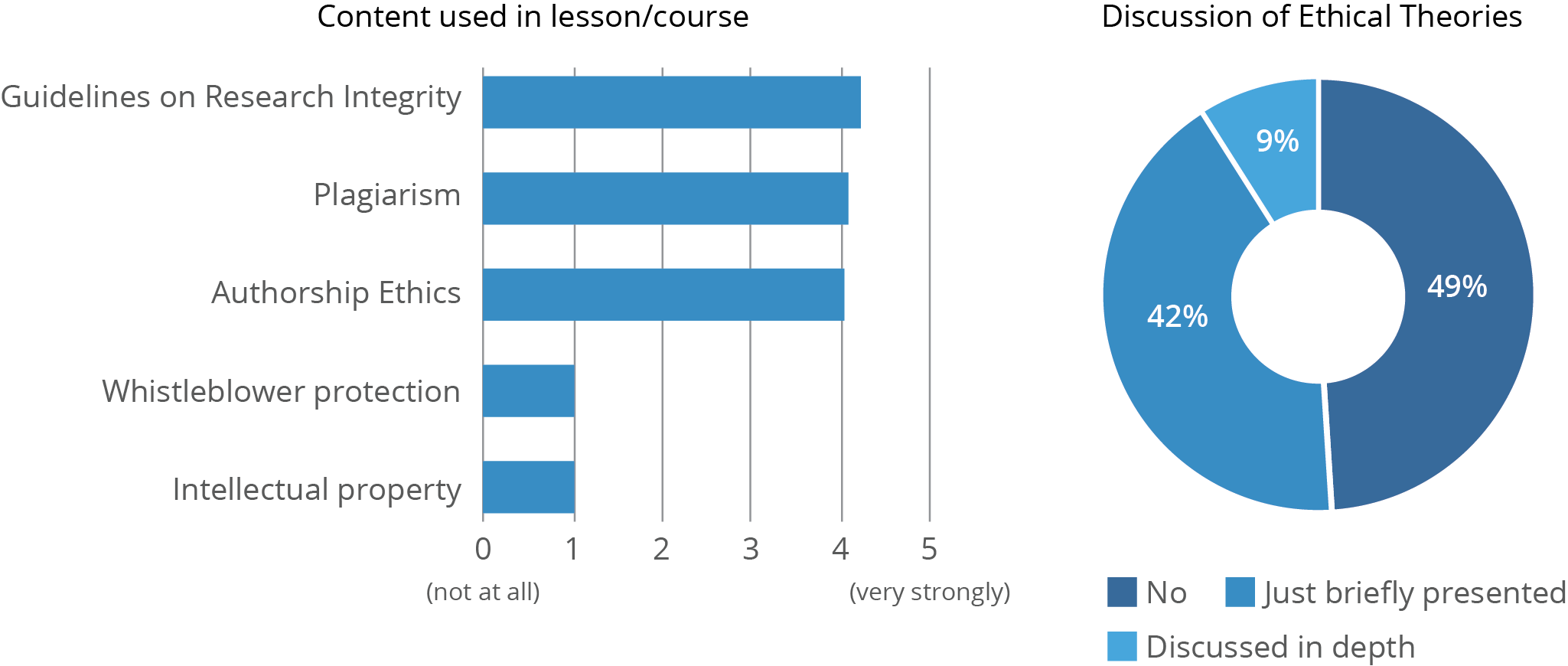

The survey was intending to gain a comprehensive picture of the teaching of research integrity in Europe, and 3 open-ended questions aiming to reveal the respondents’ personal views about the challenges they face, the potential blind spots in their teaching, and the possible ways to improve their efforts in this area. The responses from 21 European countries were gathered between June and July 2019 and provided insightful qualitative and quantitative data:

Leave a Reply